There was always going to be a point where the dual blogs would find a beautiful intersection. This is a piece that started for ‘The Authentic Leader’, and then changed. Initially published on ‘The Centre Cannot Hold’, I offer it to a different audience here.

You can find https://thecentrecannothold1.wordpress.com/ here.

In 2025, the United Kingdom is grappling with a profound and multifaceted sense of alienation, a feeling of being disconnected from one’s community, institutions, and even one’s own potential. This disassociation is not a singular phenomenon but rather a tangled web of socio-economic and political forces that manifest across three seemingly distinct domains: the classroom, the concert hall, and the political arena. By examining the education crisis, the artistic legacy of Billy Mackenzie, and the weaponisation of misinformation in political debate, a clear picture emerges of a nation grappling with a collective sense of profound disconnection.

An Analysis of the Interplay between Parental Engagement, Student Conduct, and Socioeconomic Disadvantage in the UK Education System

The UK’s education system is currently facing a significant challenge characterized by a reported behaviour and attendance crisis. This issue has moved to the forefront of political and public discourse, with government officials, including the Education Secretary, calling for a united effort involving parents, carers, and schools to get children, “at their desks and ready to learn”. While the government’s “Plan for Change” and other policy initiatives are framed as a direct response to this perceived crisis, this report deconstructs the complex and often misunderstood relationship between parental involvement, student behaviour, and social class in the UK. It moves beyond a simplistic narrative of individual responsibility to examine the deep-seated, structural factors that shape these dynamics.

The public narrative places the onus on schools and parents, yet it conveniently overlooks the systemic barriers that prevent genuine parental engagement. For many disadvantaged families, the psychological, financial, and time constraints of poverty create a profound disconnect from the school system. Parents with inflexible jobs or who are themselves products of a difficult school experience often feel like outsiders, unable to navigate the “daunting” institutional environment. This sense of alienation from the education system is then passed down to their children, who, as a result, are nearly six times more likely to be excluded. The consequence is a cycle of academic failure and social exclusion, where a child’s background becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of being left behind. In this sense, the classroom is not a place of connection and opportunity, but a field of systemic disengagement, mirroring broader societal inequalities.

This sense of disassociation and being fundamentally misunderstood is powerfully reflected in the tragic life and art of Billy Mackenzie. His hit song, “Party Fears Two,” is a masterful exploration of feeling like an imposter, a feeling of being in a room where one does not belong. The song’s beautiful, commercially successful veneer belied a deep personal struggle with anxiety and a profound aversion to the very fame it brought him. Mackenzie’s self-destructive refusal to embrace a world tour was the ultimate act of alienation—a conscious choice to reject the very system he had successfully infiltrated. His story serves as a poignant artistic mirror to a wider, national sentiment of being an outsider. In a society that often promises success and inclusion through conformity, his is a powerful example of the deep psychological cost of pretending to fit in, and the alienation that can result when one’s inner reality clashes with their public persona.

“The party fears are going to get you” From an early age, Billy Mackenzie was an outsider. Growing up in Dundee, his flamboyant style and unique vocal talent made him stand out but also made him a target. He was a flamboyant artist in a city known for its industrial grit. The “party fears” in his lyrics were not just abstract anxieties; they were a direct reflection of a deep-seated fear of social conformity and an intuitive understanding that true individuality would always be at odds with the mainstream. His artistic process itself was an act of alienation—he often worked in a hermetically sealed creative bubble, eschewing commercial advice and producing music on his own terms. This deliberate creative isolation was a protective measure, a way of ensuring his artistic vision was never compromised by the very “wolves” he would later sing about.

“I’ll buy you a drink, and then I’ll leave you for the wolves” This lyric captures the paradox of Mackenzie’s relationship with the music industry and fame. The drink is the temporary comfort of success, the brief moment of commercial validation. However, the “wolves” represent the insatiable demands of the industry—the relentless touring, the invasive media, and the pressure to conform to a pre-packaged public persona. For Mackenzie, this was a form of psychological predation that he couldn’t bear. His refusal to tour the United States after the success of “Party Fears Two” was not an act of professional incompetence but a radical statement of self-preservation, a rejection of the very system that had granted him a taste of success. He preferred to be an outsider rather than be consumed by a world that felt fundamentally inauthentic.

“I am not the one who knows you” This final line is perhaps the most devastatingly honest. It speaks to the ultimate alienation—the disconnect from oneself that comes from living an inauthentic life. It’s the moment of recognition that the person you present to the world is not who you are, a feeling of being a stranger to your own identity. For Mackenzie, who wrestled with depression and anxiety throughout his life, this lyric captures the tragic essence of his story. His art gave him a platform to be seen, but he felt unseen and unknown by the very people who celebrated him. His life, and his tragic death, is a powerful reminder that while we can connect through art, we still must do the work of connecting with each other and with ourselves to combat the corrosive effects of alienation.

Political discourse in the UK has become a primary engine of collective alienation. Political figures like Nigel Farage, through the cynical weaponisation of misinformation, actively work to sever citizens’ trust in their own institutions. By taking complex legal and political events and reframing them as personal betrayals by a faceless elite, they alienate citizens from the very systems designed to serve them. This tactic creates an environment where patriotism is no longer about a shared love of country, but a tribal loyalty test based on a hatred of “the other.” The result is a toxic form of political alienation where facts are irrelevant, institutions are illegitimate, and civil discourse is impossible. In this environment, citizens are forced to retreat from public life, further isolating themselves and losing faith in the very concept of a shared national identity.

Weaponisation of Legal Cases The cynical use of legal and political events is a key component of this alienation. A figure like Nigel Farage, for example, can seize upon a ruling from the European Court of Human Rights on the Rwanda policy. He can then deliberately misrepresent the details, framing the court as an unaccountable foreign power actively working against the British people. This is a deliberate and repeated manipulation that takes a grain of legitimate concern, wraps it in false claims, and points the finger at a convenient scapegoat. His past actions, like the £350 million bus claim for the NHS or the misinformation about EU army conscription, follow the same pattern. It is a calculated strategy to sow distrust and make people feel that their country is under siege by unseen and malicious forces.

Patriotism as Performance, Not Principle What makes this tactic particularly insidious is how it’s wrapped in a veneer of patriotism. This performative brand of nationalism is a weapon of choice for many authoritarian populists. It repackages complex policy questions as tribal loyalty tests, insisting that being patriotic means believing a politician’s lies. In this distorted view, respecting facts and the rule of law is reframed as an elite betrayal. The irony is that this manufactured narrative of betrayal is the real betrayal. When political leaders spread false information about the very institutions that protect our rights, they are attacking the foundations of democratic governance. They are teaching people to distrust the systems designed to serve them, turning patriotism from a love of country into a hatred of one’s neighbours’.

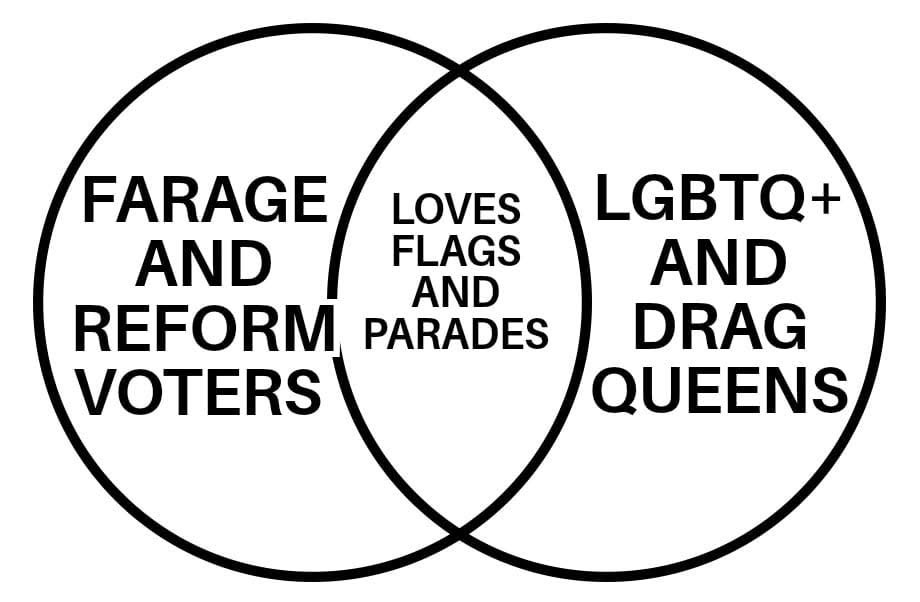

This is a mindset that manifests in tangible, public ways, perhaps most visibly in the proliferation of St. George’s flags. What was once a symbol of national pride during international sporting events is now being co-opted and stripped of its context, painted on roundabouts, or hung from windows, often in a way that feels more like a territorial marker than a unifying emblem. Similarly, The Associates’ defiant cover of David Bowie’s “Boys Keep Swinging” serves as a powerful artistic counterpoint to this. Bowie’s original was a joyful, flamboyant embrace of queer identity and self-expression. The Associates, led by the equally theatrical Billy Mackenzie, re-interpreted the song with a stark, unsettling beauty. The cover wasn’t just a tribute; it was a reassertion of the very individuality that the new, jingoistic patriotism seeks to erase. It stands in direct opposition to the simplistic, one-dimensional identity of flags on roundabouts, reminding us that true British culture is complex, rebellious, and deeply personal, not a flag to be waved in tribal displays of feigned unity.

Ultimately, the UK in 2025 is defined by a crisis of connection. From the classroom where children are left behind, to the world of art where success leads to retreat, and to the political sphere where citizens are deliberately pitted against one another, a deep sense of alienation permeates modern British life. The education crisis reveals a socio-economic alienation, the story of Billy Mackenzie highlights a psychological and artistic alienation, and the state of political discourse exposes a civic alienation. Recognizing these interconnected forms is the first step toward addressing the profound sense of disconnection that threatens to pull the nation apart.

A Checklist for a More Connected UK in 2026

As we move into 2026, here is a checklist of actionable steps that society can take to make things better for all citizens of the UK and combat the crisis of alienation, framed by a new set of guiding principles.

Elevate Intentionality

- Implement targeted, home-based support programs for disadvantaged parents to help them actively engage in their children’s learning.

- Prioritise funding for school mental health services to address the underlying causes of behavioural issues and provide support for both students and families.

- Encourage schools to use clear, jargon-free communication and build stronger, more personal relationships with parents.

- Advocate for stronger media literacy education in schools to equip citizens with the tools to identify and resist misinformation.

Combat Complacency

- Invest in community transport and public spaces to combat social and physical isolation, particularly for older citizens and those in rural areas.

- Support and amplify organisations dedicated to promoting civil and empathetic political discourse, such as Compassion in Politics.

- Promote local community initiatives that encourage face-to-face interaction and build a sense of shared purpose and identity beyond online echo chambers.

Champion Growth

- Prioritise funding for school mental health services to address the underlying causes of behavioural issues and provide support for both students and families.

- Support arts and cultural programs that celebrate diversity and provide platforms for genuine human expression, offering alternatives to the commercialized and isolating aspects of mainstream culture.

- Encourage intergenerational projects that bring different age groups together to share skills and experiences, fostering a greater sense of connection and mutual understanding.

Create Deeper Connections

- Encourage schools to build stronger, more personal relationships with parents.

- Promote local community initiatives that encourage face-to-face interaction and build a sense of shared purpose and identity beyond online echo chambers.

- Encourage intergenerational projects that bring different age groups together to share skills and experiences, fostering a greater sense of connection and mutual understanding.